In some markets there exists organisations that act as a black hole for value and profits. They are a gravity well, sucking all of the excess fat from companies above and below in the supply chain and growing their bottom line as they do it.

When I worked in telecoms, a colleague once remarked that the hardest place to make a profit in the industry is the retail division of the monopoly wholesaler. This struck me as quite counter-intuitive until he explained how value vacuums work.

How Value Vacuums Work

In many European markets, it’s very common to find a story like this…. “LaTelco” is a former state monopoly that manages all of the phone and broadband lines and infrastructure in the country. An average household can become a customer of LaTelco for home phone and broadband. To encourage competition in the market, regulations forced LaTelco to open up their infrastructure and allow other companies to re-sell broadband and phone services to local households.

This is a common regulatory move in broadband, mobile and energy markets across the world, intended to increase competition and lower prices.

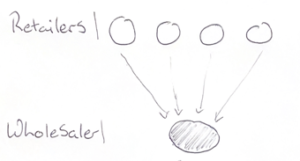

LaTelco now has two units – LaTelco Wholesale, which manages the broadband lines and physical infrastructure and LaTelco Retail, which manages customer service and billing and sales. LaTelco Retail competes with other similar retailers, all of whom are selling the same underlying service provided by LaTelco Wholesale.

Under regulation, the wholesaler has to supply services at the same rate to all retail companies. My colleague explained that the LaTelco had two choices to maximise their profits. In the first, the wholesale unit could set the price quite low. The retail unit could buy electricity cheap and sell it at a reasonable rate, then make a decent profit. This also is true of it’s retail competitors.

Alternatively, the wholesaler could set a high price, making a high profit for itself. It would squeeze all the profit out of it’s own retail arm, which isn’t ideal, but it would also squeeze the profit out of the retail competitors.

It’s not hard to see what the optimal strategy is here, and which the parent company would often chose. In the second option they can use their pricing power to capture the excess value in the entire market, rather than just the market share of it’s retail unit in the first option.

All of the profit in the top layer is sucked down to the wholesaler

This is why my friend’s job, as a manager tasked with making the retail unit profitable, was a tough one!

In cases like these, wholesale supplier can act as a Value Vaccum, hoovering up all the profits from the companies they supply.

From a societal perspective, this is very far from ideal. Why should the retailers continue to innovate, cut costs or improve service, when every bit of margin they generate will ultimately accrue to the layer below them?

Why McDonalds is a Real Estate Company

Ray Kroc, the first CEO of McDonalds, famously hit on this realisation in 1956 when he changed the business model of the McDonalds franchise system. Instead of trying to make his fortune from a small percentage of each burger sale, he instead started buying the land on which each McDonald’s franchise was built and locking the franchise owner into a long-term lease.

By owning the land, Kroc was able to use rent prices to capture the lions share of value created by each restaurant.

Tren Griffin, who calls this effect “Wholesale Transfer Pricing,” shared a story of the Wild Ginger restaurant in Seattle

The restaurant was a huge success. When lease renewal time came up for Wild Ginger the landlord wanted a massive rent increase. The ability of the landlord to demand that increase is wholesale pricing power.

In this situation, people often have the option to move premises (at great cost), but in times of limited supply, like now, Land can act as the ultimate vacuum because, as Mark Twain noted, they’re not making it any more.

In times like these, the technique Ray Kroc used to capture the majority of value created by restaurant owners is now happing at a society wide level.

Land owners are capturing huge amounts of the value that productivity growth is creating in society.

Look at San Francisco, for example. Young workers are getting huge salaries from tech companies, but paying huge amounts of that out in rent. Huge amounts of the value created by the tech revolution should be accruing to workers, but is instead hoovered up in Value Vacuums by land owners, who played very little part in the creation of that value.

There are, of course, ways to weaken the power of Value Vacuums. Introducing competitors, regulations and price controls, and even wider shifts like the introduction of remote working, or the provision of public transport, can alter the dynamics.

Value Vacuums are something we should always be mindful of, to combat their ability to distort markets and separate value creation from value capture.